Moment's Notice

Reviews of Recent Recordings

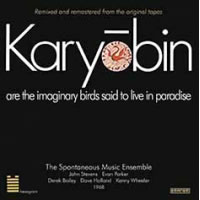

Spontaneous Music Ensemble

Karyōbin

Emanem 5046

To an almost comical degree, the Spontaneous Music Ensemble’s Karyōbin touches on so much going on musically in 1968. Martin Davidson’s, Evan Parker’s and Dave Holland’s annotations to a new reissue help put it in perspective. Island Records’ emerging pop mogul Chris Blackwell commissioned it as the flagship release in his new Hexagram imprint devoted to London free music. Engineer and co-producer Eddie Kramer had recorded the Beatles and Stones as they branched into psychedelia, and was now busy with Jimi Hendrix. While SME were recording, Yoko Ono came by the studio, apparently on some mission concerning her upcoming London concert with Ornette Coleman. Karyōbin is also situated at the grand intersection of jazz and European improvised music, rounding one boulevard onto the other, a change in direction.

That Sunday in February, drummer John Stevens’ SME was a quintet. The date was the first issued recording by Parker, on soprano saxophone, which also makes it his first record with guitarist Derek Bailey, who’d go on to be his sparring partner for as long as they could stand each other – another 17 years. Seven months after this session bassist Holland was recording with his new boss Miles Davis in New York. Holland and Karyōbin trumpeter Kenny Wheeler, the band’s seasoned jazzman, would keep meeting up in diverse settings before and after they reunited in Anthony Braxton’s breakthrough quartet in 1974 (the year Braxton and Bailey played Wigmore Hall), and in Holland’s ’80s quintet. Post-Karyōbin Wheeler also continued to improvise with Evan and Derek, and later he brought Parker in to make a memorably explosive entrance on his 1979 ECM album Around 6, where his sputtering episode hijacks the whole piece. Evan’s arrival’s as disruptive as the alien interrupting John Hurt’s lunch that same summer.

©Jak Kilby

After Karyōbin Holland and Wheeler mostly kept to the jazz side of the fence, while the other three conspicuously went another way. Karyōbin helped proclaim the new co-operative English model for improvised music. Producer Davidson recalls Evan’s 1997 formulation of John Stevens’ precepts: if you can’t hear someone else you’re too loud; if you don’t reference what your mates play sometimes, you may as well not bother. This esthetic was in marked contrast to German aural machine-gunning and Dutch kitchen-sinkism/oppositionalism. The combative Bennink-Mengelberg duo practically embodies an anti-Stevens esthetic.

Just about the first thing you notice here is, everyone’s listening. The music is joyously cohesive; the perfectly formed, rubato opening phrase, four seconds and a dramatic pause for five players stepping off together, is a gem to stop you short. The whole eight-minute improvisation is a marvel. The players’ search for a quieter way, if nothing else, ties this music to (more compositionally-oriented) contemporary developments in African American Chicago. In some later co-operative UK improvising, the respectful quietude could get uniformly grey. On Karyōbin dynamic range is one more parameter to play with.

Parker and Wheeler exploit the extensive overlap between the ranges of soprano sax and trumpet or flugelhorn; they often reach out to each other, embracing communion in long tones and molded swoops. Evan might reference or even quickly chase Kenny’s characteristic overshot octaves and other wide intervals. Did Steve Lacy ever speak of SME’s influence? Karyōbin’s gleeful glow of two horns in the same register, squeezing narrow intervals between them, looks ahead to his frictive blending with Steve Potts in the scrappy early ‘70s. To these ears the interplay of winds on Karyōbin is beyond what Lacy’s soprano and Enrico Rava’s trumpet got up to four months before, recording The Forest and the Zoo, with its similar free method and instrumentation.

Davidson confidently asserts Karyōbin “sounds totally unlike jazz,” and it’s certainly true that Holland plays bass as a melody instrument, studiously avoiding functional walking, let alone those vampy ways he’d structure spontaneous play with Sam Rivers in the ‘70s. Rather he displays the nimble, precise, rapid yet melodic lines, admirably clear consistent attack and eerily sure intonation he’d soon be famous for – those, and jazz-informed timing. A fast bass on the bottom keeps everyone moving, reduces risk of stalling.

Old mother jazz was not quite so easy for the English (or Germans) to leave behind as they seemed to think. (The Dutch maniacs gave it up for about five minutes – they missed the swinging, and good tunes.) It was as if, having played jazz first, some Euro-improvisers never noticed that playing a string of improvised solos in a two horn/three rhythm quintet including drum set betrayed a certain lingering influence. As Davidson allows, a trumpet-saxophone-guitar-bass-drums line up is suggestive; swap clarinet in for soprano and this starts to resemble Buddy Bolden’s bunch. And in the collectives, even flinty old dance-band-refugee Derek may sketch in a light harmonic background or suggest a pedal point. (It would hardly be the last time he’d reference his jazzy side; barely three minutes into Beak Doctor’s new LP of 1992 duets with pianist Greg Goodman, Extracting Fish-Bones from the Back of the Despoiler, the guitarist hits a skippy shuffle rhythm and sounds ready to jump into “Misterioso.”)

What struck me most, listening to the new sonically scrubbed edition that brings more clarity to bass and drums, is how much jazz remains in John Stevens’ sound. Or rather, you can hear the atomization of jazz rhythm in it: one rhythmic language reconfiguring into another, a new dialect forming before your ears. Stevens made a decisive turn away from free play’s bombastic side with a quieter kit using smaller drums, but (as Parker’s session photos show) for this date he brought a large array, including what looks like six cymbals/gongs plus hi-hat. Even drummers with pared-down kits don’t always skimp on the shimmering metal, and on parts 1 and 6 in particular, Stevens’ nervous cymbal chatter makes for a kind of non-dictatorial pulsation not entirely unrelated to Kenny Clarke: a free-music ride-cymbal beat. It comes and goes, but it’s there rather a lot, and everyone responds to it some kind of way. This music moves.

There are different ways of making it move; that more fully atomized mode the English were working toward, that Derek perfected, that affected even Evan’s ceaseless circular solo miracles, is in here too. One of the glories of Karyōbin is that you can hear how Dave Holland would carry the more immersive, textural, surging but harmonically static kind of collective improvisation (as displayed on part 4) into a whole other context: Miles Davis’ (belatedly) celebrated fusion of free and funk onstage at the Fillmore, three years later.

Karyōbin is so strong, there had to be moments before it came out when the players thought, we’re all set now: this is gonna be the next big thing. The LP didn’t sell big of course, and proved to be the lone Hexagram release. But as far as being the next big thing? They totally nailed that.

–Kevin Whitehead