Omnidirectional Projection: Teruto Soejima and Japanese Free Jazz

by

by Pierre Crépon

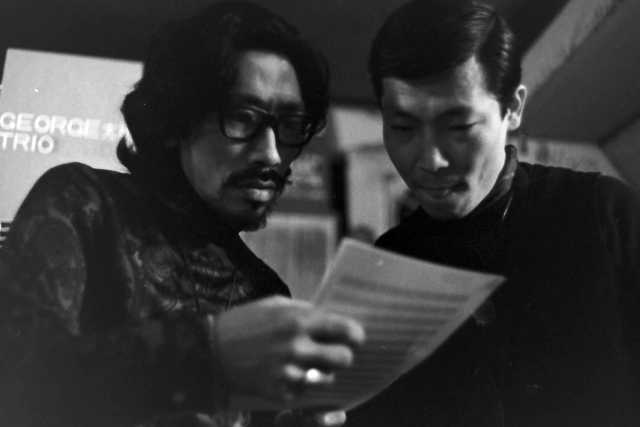

Motoharu Yoshizawa + Mototeru Takagi © 2019 Tatsuro Minami

The second side of Pharoah Sanders’s Tauhid starts with a short track titled “Japan.” The pseudo-Asian piece was recorded a few months after Sanders’s return from a Japanese tour with John Coltrane, in 1966. By the time of the Sanders session, free jazz was about to gain a significant new branch in the country which had inspired the composition. This is the story told by critic and promoter Teruto Soejima in Free Jazz in Japan: A Personal History (Nara: Public Bath Press, 2018), originally published in Japanese in 2002 (1) and now translated by Kato David Hopkins.

After an introduction by Otomo Yoshihide, the book opens with a rapid prehistory of Japanese free jazz. Mentioned are the contemporary music influenced New Music Research Lab and its early sixties Ginparis club sessions; the opening of Jazz Gallery 8 in 1964, a forward looking club operated by musicians; and a short-lived unrecorded quartet led by drummer Masahiko Togashi in 1965, giving “possibly the first truly free jazz performance in Japan.” (2)

In 1966, the Pit Inn club opened in Tokyo’s Shinjuku district. It was where pianist Yosuke Yamashita’s band, whose music was then a mix of modern and avant-garde jazz, would soon start to be heard. Bassist Motoharu Yoshizawa’s trio followed in 1968, and 1969 was the year the story as told by Soejima truly begins, when a small pool of avant-garde musicians coalesced in several, often overlapping units. Togashi and pianist Masahiko Sato co-led ESSG, a quartet with saxophonist Mototeru Takagi and trumpeter Itaru Oki; Yamashita launched the first incarnation of what would become his classic trio; and guitarist Masayuki Takayanagi started his New Direction Unit.

A passing acquaintance with free jazz generally elicits an association with the idea of intensity. Japanese free jazz can be intense intense music. “This was truly free jazz,” Soejima writes of ESSG, “one night they played for three hours straight with no intermission ... They played on with all of their mental and physical strength, throwing everything they had. The audience held its breath, fearing the musicians would collapse. And then suddenly, a long silence. A silence full of tension, as if the sounds of nothingness was racing through their consciousness. A metaphysical sensation. Before we knew it, we could just barely hear Togashi’s cymbals lightly ringing, or was it merely a hallucination?” (3) An anecdote has the members of the Duke Ellington Orchestra dropping by the Pit Inn during a tour, sitting motionless for an ESSG set before leaving with stunned expressions on their faces.

Takayanagi’s New Direction Unit, originally a trio with Yoshizawa and drummer Sabu Toyozumi, “centered their activities on the jazz coffee shop Nagisa, near the south exit to Shinjuku station. Because of the volume of their playing, and their uncompromising approach free of melody and rhythm, they weren’t blessed with many chances to play in more traditional jazz spaces. Nagisa was like a hangout for hippies and street people, and people who were high on Haiminaru sleeping pills, still legal at the time, could be seen nodding off, sometimes even on the stage ... The sound was so loud that the paint on the ceiling, shaken by the vibration, would flake off and fall like snow on the heads of the audience.” (4)

Takayanagi directed his musicians to constantly play fortissimo, not repeat any phrases, and forbade listening to other members of the group to play along. This extremely radical approach was certainly far removed from what was going on in New York free jazz, played in its birthplace or in its Paris transplantation, or even from the free improvisation developing in Britain.

A number of important records were made that 1969 year: Togashi’s We Now Create (Victor World Group), Sato’s Deformation and Palladium (Toshiba/Express), Yamashita’s Concert in New Jazz, Togashi’s Speed and Space (although not credited to ESSG, a close reflection of its sound), and Takayanagi’s Independence (the latter three released by Teichiku/Union). Adding Yoshizawa’s unrecorded group, this list amounted to pretty much the complete work of the founding era, Soejima writes.

In November 1969, the author was involved in the conversion of an instrument storage room on Pit Inn’s second floor into a live spot dedicated entirely to free playing. “New Jazz Hall” could sit an audience of fifty, and would be programmed with an experimental approach, close to open rehearsals. The initial rotation featured ESSG, New Direction Unit, Yoshizawa’s trio, and another trio led by Itaru Oki. Togashi and Sato continued to headline at the Pit Inn downstairs, but would let loose at New Jazz Hall.

The Shinjuku spot quickly attracted new musicians, perhaps most notably saxophonist Kaoru Abe. The unique alto sound he produced using an extremely hard reed started to be heard there on a weekly basis in 1970. Abe played at first mainly solo, a modus operandi which in a way continued even inside formations, as he placed no emphasis on group sound. Abe’s was not the sound of surprise, but of estrangement. The pages dedicated to the saxophonist shed some light on his personality, through Soejima’s memories and direct quotes. Asked by Swing Journal what he was trying to express in his music, Abe answered: “How to have a sound that stops all judgment. A sound that doesn’t disappear. A sound that weaves through all kinds of images. A sound with presence. A sound that is forbidden forever. A sound that can’t be owned. The sound of going insane. A sound full of the cosmos. The sound of sound.” (6)

Although he discusses records extensively, as a protagonist of the scene Soejima is not bound by discographical limits. The sparsely recorded Now Music Ensemble, belonging to what was already a second generation of free players, is covered at length. Its goal of “complete deconstruction of the normal performance style, including that of free jazz,” (6) intense stage presence and physicality, use of theatrics, objects-as-instruments, and conceptual pieces made NME very popular with student activists, leading to numerous appearances at universities and a status as one of the marking groups of the era.

The book was not written for Western audiences, and readers unfamiliar with Japanese history will sometimes need to look things up. The Shinjuku backdrop is important, as are the clashes between the helmeted student activists of the Zenkyoto and the riot police that peaked in 1968-1970, also a period of indefinite strikes and occupations on campuses. (7) Filmmakers Koji Wakamatsu, whose “pink films” include appearances by Yamashita and Abe, and Masao Adachi, for whom Togashi made his last recording before suffering a spinal cord injury that left him paralyzed from the chest down in 1969, are among the names worth researching further.

New Jazz Hall audiences were sometimes very sparse, but it became a hangout for avant-garde artists such as director Nagisa Oshima of future In the Realm of the Senses fame. The spot and its “way, way out, experimental jazz” somehow managed to garner an in-passing mention next to Pit Inn and Taro in a 1971 New York Times piece on Shinjuku, casting the area as “Tokyo’s Manhattan, an odd but enchanting combination of Greenwich Village, the Garment District and Park Avenue compressed into a few square miles.” (8)

Other New Jazz Hall activities included performances by the mostly untrained musicians of the Taj Mahal Travellers, the Takagi/Toyozumi duo, Sato’s synthesizer trio Garandoh, experiments with large ensembles, events featuring poets, and showings of underground cinema (filmmaker Jonas Mekas gets a mention). The book offers glimpses of moments including the first Japanese/European free jazz junction point, with German musicians Manfred Schoof and Gerd Dudek sitting in at New Jazz Hall during a Goethe-Institut tour, and pianist Ryo Hara embarking on a chaotic trip with a piano mounted on a truck, as free jazz was starting to travel outside of the confines of Tokyo.

The club, whose story occupies close to a third of the book’s 350 pages, closed in the summer of 1971, after just a year and a half of operation. Soejima’s activities then moved to Pulcinella, a piano-less spot on the third floor of a Shibuya district building occupied by a puppet theater. Similar programs continued, with the addition of new players such as saxophonists Akira Sakata and Kazutoki Umezu, and trumpeter Toshinori Kondo. The first half of the seventies brought a less radical and political climate, reflected at Pulcinella by scarcer audiences. In 1973, Soejima gathered musician associates and proposed making a large-scale move to prevent the music from fading away.

This led to the staging of Inspiration & Power 14, a festival presenting most of Tokyo’s free jazz musicians for two weeks in a Shinjuku arthouse cinema. In his wheelchair, Togashi made his return as a percussionist to the large stage; a double album memorialized the events, but it did not initiate a growth in the popularity of the music.

Some musicians started to venture overseas. Takagi and Oki traveled to France (where the trumpeter can still be heard with the likes of pianist François Tusques and drummer Makoto Sato). The Yamashita trio started to tour Europe in 1974, making an impact particularly in Germany. Soejima himself initiated a relationship with the Moers festival. Togashi established an international reputation, working with major visiting musicians such as Don Cherry and Steve Lacy. In 1975, he recorded his landmark Spiritual Nature album. In the US, ESP-Disk’s Bernard Stollman expressed interest in making a series of recordings featuring Japanese musicians after having heard the Inspiration & Power 14 anthology. A Takayanagi recording was produced, but the label folded, pushing the release back by 15 years.

A second Inspiration & Power festival was staged in January 1976, giving complete carte blanche to the musicians, who were only asked to do something they had not done before and participated in the production. Soejima details the proceedings at length, but even if for him the festival surpassed the first installment, a financial deficit ensued, and a subsequent statement was not attempted.

The last three chapters of the book feel more fragmented, probably because of a greater difficulty to identify underlying trends. Themes include a glimpse at increased international connections, notably through the work of another writer and promoter figure, Akira Aida, who brought artists such as Steve Lacy, Milford Graves, and Derek Bailey to Japan. Aida’s work was cut short by his sudden death in 1978, just months after Kaoru Abe overdosed on sleeping pills.

Increased export possibilities were taken advantage of in the eighties by musicians fitting what Soejima dubs the “pop avant-garde,” using the art world acceptation of the “pop” term. The trend, including the Doctor Umezu Band and Yoshiaki Fujikawa’s Eastasia Orchestra “brought the beat back. This wasn’t a return to the four-beat or eight-beat of once upon a time jazz, however. It was open to rock, tango, samba, any kind of rhythm from anywhere in the world. Melodic themes were also back, but soloing was an intensely personal affair ... This was a sound that could only be made after passing through the crucible of free jazz. There were new ways to conceive of the role of a group structure and how an individual voice might be expressed in that context.” (9)

Similarly, Soejima tries to delimit a “borderless music” involving people like John Zorn and Masahiko Sato in genre crossing collaborations making use of folk and electronic instruments. But, “as territory becomes more vaguely defined, things that can be seen as free jazz also become more difficult to distinguish.” (10)

The pioneers of Japanese free jazz were by then established and continued to travel their personal paths. Togashi could be found improvising a drum solo soundtrack to a three-hour Shinsuke Ogawa documentary, Takayanagi created his Angry Waves trio before moving to solo explorations of sound using the Action Direct name. Takayanagi died in 1991, and Motoharu Yoshizawa in 1998.

The book ends with a short overview of the scene at the time of the writing and some reflections on the author’s own work.

Generally speaking, the density of the book fluctuates, both in subject matters and in form. Numerous instances of Soejima’s previous writings, liner notes or articles, are woven into the fabric of the text and do condition the space devoted to certain topics. Emphasis is also placed on presenting the musicians in their own words, players make direct contributions, but they are unfortunately often unclearly sourced.

Soejima’s book was originally subtitled “The History of Japanese Free Jazz.” The publisher wisely opted for a change to “A Personal History” reflecting how strongly the author’s personal lens and own work impact the way the story is told and what is covered. Important musicians such as Takayanagi or Yoshizawa slip out of the picture at times because of interpersonal factors, and although external sources such as magazine articles are used, it does not seem like systematic research was conducted to try to present an all-encompassing perspective. Soejima’s book is part memoir and part history.

For unknown reasons, the author does not mention archival releases that were already available at the time of his writing, such as PSF’s J⋅I⋅コレクション series, although it includes Kaoru Abe recordings at New Jazz Hall (11) and Pulcinella (12), or a 1969 Yoshizawa duet with Mototeru Takagi that fills a void in the recordings issued at the time. (13)

Retaining the original “Japanese Free Jazz” rather than “Free Jazz in Japan” of the title would probably have been more accurate, as everything outside of the music made by Japanese musicians is at best given passing mention. We do not learn how American free jazz arrived in Japan, how it was received, circulated, or even the precise nature of the relationship Japanese musicians entertained with it. The quasi-complete absence of Coltrane’s 1966 tour with Pharoah Sanders illustrates this point. (14) Without committing the usual error of assuming that everything has to be derivative of American accomplishments, certainly the music brought by Coltrane in person must have had some impact, as it did on a worldwide scale. Swing Journal devoted covers to Marion Brown, Don Cherry, Albert Ayler, Sanders, and American free jazz’s presence in Japan will hopefully be the topic of future scholarship. Similarly, it is to be hoped that more instances of the literature on free jazz existing in Japan will become available to English speaking audiences. (15)

Although the music seems to have been very well documented on tape since its beginnings, the author’s involvement in the scene allows him to go beyond the discographical narrative, discussing the work of bands as living entities, and in the process giving a sense of the finite aspect of music making. A discography would have been a welcome appendix, but none is provided and making notes of discussed titles will be necessary.

Soejima at times evokes the music more poetically, but his approach generally focuses on the concepts at play, interestingly described from a non-musician perspective. The multiplicity of approaches to which combinations inside an overall small pool of players gave birth is notable and give important food for thought.

The book is illustrated by historical pictures shot by photographers Tatsuo Minami and Masahiro Mochida.

Intriguingly, Soejima seems to consider “free jazz” as a defined object with set parameters, existing in the abstract, that Japanese musicians progressively managed to capture, giving birth in the process to original music, the essence of the free jazz creative act. There would be much to discuss about this topic. No manual was ever issued to guide aspiring musicians, and when the idea of a freer jazz spread around the world, it is quite possible that the wide diversity of music it engendered came in good part from differing relationships to an idea rather than to a strictly defined form. The case of the Now Music Ensemble exemplifies this: the concepts at play had seemingly little to do with the music played in the United States, whether in intent or in form.

Free Jazz in Japan is the only attempt at a detailed history of one of free jazz’s most original branches available in English. Although it is also a deeply personal take, Public Bath Press has done a great service to listeners by allowing non-Japanese audiences to learn more about the context in which an important part of a now global music developed. Ultimately, Soejima’s work is a book dealing with a radical questioning of all aspects of jazz in an intense quest for the “new,” a quest from which there is much to hear.

Notes

1. Teruto Soejima, 日本フリージャズ史: The History of Japanese Free Jazz (Tokyo: Seidosha, 2002).

2. Soejima, Free Jazz in Japan, 18. On this era, see also E. Taylor Atkins, “Our Thing: Defining ‘Japanese Jazz,’” chap. 6 in Blue Nippon: Authenticating Jazz in Japan (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001).

3. Soejima, Free Jazz in Japan, 48.

4. Soejima, Free Jazz in Japan, 68-69.

5. Soejima, Free Jazz in Japan, 95.

6. Soejima, Free Jazz in Japan, 104.

7. See Patricia G. Steinhoff, “Japan: Student Activism in an Emerging Democracy,” in Student Activism in Asia: Between Protest and Powerlessness, ed. Meredith L. Weiss and Edward Aspinall (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 57-78.

8. Neil A. Martin, “The Brilliant Subculture of Tokyo’s ‘Underground Town,’” New York Times, March 7, 1971, XX3, XX31, https://www.nytimes.com/1971/03/07/archives/the-brilliant-subculture-of-tokyos-underground-town-underground.html.

9. Soejima, Free Jazz in Japan, 295.

10. Soejima, Free Jazz in Japan, 315.

11. Kaoru Abe Trio, 1970年3月, 新宿, PSF PSFD-56, 1995, CD.

12. Kaoru Abe, 光輝く忍耐, PSF PSFD-46, 1994, CD; Kaoru Abe, 木曜日の夜, PSF PSFD-66, 1995, CD.

13. Motoharu Yoshizawa/Mototeru Takagi, 深海, PSF PSFD-47, 1994, CD.

14. See Katherine Whatley, “Tracing a Giant Step: John Coltrane in Japan,” Point of Departure, no. 57 (December 2016), http://www.pointofdeparture.org/PoD57/PoD57Coltrane.html.

15. For example, three volumes compiling Akira Aida’s multi-genres writing have been published under the title 間章著作集 I-III (Chōfu-shi: Getsuyosha, 2013-2014); Masayuki Takayanagi’s writings have been compiled as 汎音楽論集 (Chōfu-shi: Getsuyosha, 2006); and texts by critic and promoter Toshihiko Shimizu are available as ジャズ・アヴァンギャルド: <em>Jazz Avant-Garde Chronicle 1967-1989</em> (Tokyo: Seidosha, 1990).