Moment's Notice

Reviews of Recent Media

(continued)

Whit Dickey

Astral Long Form: Staircase In Space

TAO Forms TAO 09

Drummer Whit Dickey has a habit of assembling potent bands, and the outfit he’s corralled on Staircase In Space is no exception. Although largely a collection of familiar faces with long joint working histories, this was the first time all four had been in the studio together. Alto saxophonist Rob Brown and violinist Mat Maneri have been regular sparring partners for decades, during which time Dickey has dispensed with charts entirely, instead relying on the considerable improvising talents of his colleagues. In this context bassist Brandon Lopez constitutes the wild card. His association with Dickey harks back somewhat less to 2020 when he appeared on Dickey’s trio date Expanding Light, alongside Brown.

Drummer Whit Dickey has a habit of assembling potent bands, and the outfit he’s corralled on Staircase In Space is no exception. Although largely a collection of familiar faces with long joint working histories, this was the first time all four had been in the studio together. Alto saxophonist Rob Brown and violinist Mat Maneri have been regular sparring partners for decades, during which time Dickey has dispensed with charts entirely, instead relying on the considerable improvising talents of his colleagues. In this context bassist Brandon Lopez constitutes the wild card. His association with Dickey harks back somewhat less to 2020 when he appeared on Dickey’s trio date Expanding Light, alongside Brown.

Dickey spontaneously orchestrates the five tracks from behind the trap set, traversing the sort of expanses without tune or meter which come as second nature to this crew. Dizzy Gillespie is reputed to have said: “It’s taken me all my life to learn what not to play.” And both here and elsewhere (2021’s Village Mothership springs to mind) Dickey certainly seems to have reached a new level through playing less. By leaving a lattice of space he also promotes openness and transparency that allows full appreciation of all the components. But having initiated the movement, he trusts in his comrades and follows as much as leads, as roles mutate in a continuous flux where each episode contains the seeds of the next, but germinates in unpredictable ways. While intensity abounds, it’s achieved not through density or extremes of volume, but rather through the oblique sinewy connections between the ricocheting and disorientating parts.

And what parts! Dickey’s timbral command extends to shuffles, rattles, chatter, thwacks, and accents, sometimes concurrently on different elements of his kit. His brief bursts of time and texture, variously comment, steer, and prompt. Lopez proves a willing accomplice to Dickey’s abstraction, his seesawing arco swoops and simultaneously voiced strings especially grabbing the ear. However, Brown demands almost constant attention. He’s one of the few who can maintain an unfurling flow without resorting to regular repetition. Everything convinces as freshly minted. With his fractured notes and sour sweet tone, he’s also, perhaps unintentionally, perfected the querulous, anxious sound of alienation, aptly evoking the uncertain zeitgeist. Maneri only increases the discomfort. Totally sui generis as an improviser, his emotionally ambiguous lines excavate the strata between pitches often suggesting melancholy or disillusion.

So, there are no jolly ditties or heartfelt ballads to hum along with, but what makes this set worthwhile are the compelling and continually evolving dialogues, whether that be the extemporized counterpoint between Brown and Maneri which frequently surfaces during the program, or the creaking fidgety exchanges between Maneri and Lopez, like that which introduces “Space Quadrant.” Then of course there’s Dickey, who seems in perpetual conversation with everyone. His whacked interjections among Maneri’s halting phrases on “The Pendulum Turns” are particularly notable. It’s another fine addition to the drummer’s discography.

–John Sharpe

Dave Douglas

Secular Psalms

Greenleaf GRE-CD-1090

Commissioned by the City of Ghent and Handelsbeurs Theater to commemorate the 600th anniversary of The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (better known as the Ghent Altarpiece), by Jan and Hubert van Eyck, Dave Douglas invited an international cast of young musicians to work with him on Secular Psalms, a song suite inspired by the famous altarpiece. The Ghent Altarpiece was originally painted for display in St. Bavo’s Cathedral in Ghent, Belgium, and completed in 1432, just after the plague which devastated Europe in the late 14th century. Jan van Eyck is renowned as one of the first masters of portraiture, but in the Ghent Altarpiece he and his brother captured a scene representing all classes of society.

Commissioned by the City of Ghent and Handelsbeurs Theater to commemorate the 600th anniversary of The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (better known as the Ghent Altarpiece), by Jan and Hubert van Eyck, Dave Douglas invited an international cast of young musicians to work with him on Secular Psalms, a song suite inspired by the famous altarpiece. The Ghent Altarpiece was originally painted for display in St. Bavo’s Cathedral in Ghent, Belgium, and completed in 1432, just after the plague which devastated Europe in the late 14th century. Jan van Eyck is renowned as one of the first masters of portraiture, but in the Ghent Altarpiece he and his brother captured a scene representing all classes of society.

The core musical foundation of Secular Psalms is the religious music and secular songs of Renaissance composer Guillaume DuFay, a friend of van Eyck, while lyrical inspiration on half the numbers derives from the Latin Mass and the poetry of Christine De Pisan, a member of the Burgundian court who likely knew the famous painter. Douglas’ research of the Altarpiece revealed that panels were moved, stolen, and recovered over the years, while a 2012 restoration uncovered that the work was overpainted around 1550. The removal of the overpainting unveiled a new view of the piece – layers of history that Douglas channels in his electro-acoustic interpretation, pitting pump organ and serpent against efx-laden guitar and electronic samples.

The suite follows a visual narrative, with the muted colors and dark textures of “Arrival” making way for passages of electrifying brilliance, before ultimately concluding with the dramatic tone poem “Ah Moon” and the regal finale “Edge of Night.” In-between, Berlinde Deman’s forlorn vocals on the inspirational “Mercy” invoke Psalm 59 as well as Marvin Gaye’s “Mercy Mercy Me,” with Douglas’ trumpet leading Frederick Leroux’s searing fretwork and Tomeka Reid’s sinewy cello through mercurial rhythm changes and kaleidoscopic harmonies. “We Believe,” sung by Deman in Latin, is underscored by Marta Warelis’ rich pump organ harmonies and contrapuntal commentary from Reid’s cello and Leroux’s lute. Based on DuFay’s mathematically complex pieces, drummer Lander Gyselinck and Reid navigate shifting polyrhythms on “Agnus Dei,” driving impassioned solos from Douglas, Warelis on piano, and Leroux on distorted guitar. Similarly, the hocketing latticework of “Instrumental Angels,” angular detours of “Hermits and Pilgrims,” and whimsical electronic flourishes of “Righteous Judges” further Douglas’ compositional gambit, underpinning religious solemnity with secular passion.

In a conceptual parallel, the Black Death delayed the completion of the Ghent Altarpiece in much the same way that the global pandemic effected Secular Psalms, forcing each musician to record their parts separately, in three different countries. As such, the project gained additional poignancy for Douglas, who stated that the album contains “songs of praise for all of us as we are.” The concluding “Edge of Night” sums up this sentiment with the lines “Making this music will help us to heal/Even as the world continues to reel.” Drawing on the Latin Mass, early medieval folk songs, DuFay’s compositions, and contemporary jazz and improvised music, Douglas and company deliver an optimistic score for troubled times.

–Troy Collins

Christopher Fox

Hieroglyphs

ezz-thetics 1030

Christopher Fox has covered the waterfront of contemporary composition for decades, resulting in a wealth of works that touch upon much of what has endured beginning in the Elizabethan age through Minimalism. In the process, he has managed not to be reduced to mere eclecticism by using a consistently stringent filter with whatever inspires him for a given piece, and by constantly changing his conceptual bearings, which frequently entails new instrumental palettes. On the recent compositions collected on Hieroglyphs, Fox touches upon Welsh folk music, Thomas Tallis, and microtonality; he also augments the chamber music staples of violin, cello, and piano with tenor saxophone and electric guitar, resulting in music that is both subtle and bold.

Christopher Fox has covered the waterfront of contemporary composition for decades, resulting in a wealth of works that touch upon much of what has endured beginning in the Elizabethan age through Minimalism. In the process, he has managed not to be reduced to mere eclecticism by using a consistently stringent filter with whatever inspires him for a given piece, and by constantly changing his conceptual bearings, which frequently entails new instrumental palettes. On the recent compositions collected on Hieroglyphs, Fox touches upon Welsh folk music, Thomas Tallis, and microtonality; he also augments the chamber music staples of violin, cello, and piano with tenor saxophone and electric guitar, resulting in music that is both subtle and bold.

The album is bookended by two multi-section works for contrasting trios extracted from Ensemble SEV. Beyond the title “This is the Wind” and material in their respective first movements, they share performances by cellist Dan Weinstein and little else. The album-opening version is scored for violin, cello, and piano, and is the more astringent of the two. Weinstein, violinist Yael Barolsky, and pianist Ido Akov sustain a timbre-rooted tension, whether evoking the harshness of Welsh farm life or the huge empty spaces of Lamonte Young’s Idaho. The second version – performed by Weinstein, tenor saxophonist Jonathan Chazan, and electric guitarist Dennis Sololev – is initially headed along a similar arc until the last section, “Palmyra,” a collage created by snippets of Tallis’ settings of the Book of Lamentation. Fox’s observation that the performers “piece together these shards of Tallis’ music, trying to make them into a coherent shape” goes to the heart of what is compelling about the closing piece. Tallis’ reverence survived deconstruction. Fox gave it a new depth.

In between the new takes on “This is the Wind,” there are two lengthy solo pieces, “Planes and Folds” for violin, and the title piece for cello. Barolsky brings the soul of Eastern European fiddling to the former, but it informs the materials instead of saturating them. Weinstein’s performance reinforces the emotional tenuousness of the pieces. They are equally rewarding. The album is laced together by three duo tracks by Barolsky and Weinstein, each consisting of two parts of Fox’s “Paralogos” sequence; written as commentaries on other music, they emphasize what are commonly referred to as extended techniques, though in the 21st Century they have become staples for composers and improvisers.

–Bill Shoemaker

Jacob Garchik

Assembly

Yestereve 07

Well-known for his eclectic body of work, trombonist Jacob Garchik’s recent series of concept albums have tackled rhythm section-less big bands (Clear Line, 2020), prog-metal (Ye Olde, 2015), and gospel (The Heavens: The Atheist Gospel Trombone Album, 2012), all released on his own Yestereve imprint. Garchik’s latest effort, Assembly, may be his most jazz-oriented album yet, albeit one still imbued with his mercurial sensibility.

Well-known for his eclectic body of work, trombonist Jacob Garchik’s recent series of concept albums have tackled rhythm section-less big bands (Clear Line, 2020), prog-metal (Ye Olde, 2015), and gospel (The Heavens: The Atheist Gospel Trombone Album, 2012), all released on his own Yestereve imprint. Garchik’s latest effort, Assembly, may be his most jazz-oriented album yet, albeit one still imbued with his mercurial sensibility.

In February 2021, amidst the throes of the pandemic, Garchik found a recording studio with enough isolation booths to safely record a quintet. Augmenting his working trio of pianist Jacob Sacks and drummer Dan Weiss with bassist Thomas Morgan and soprano saxophonist Sam Newsome, Garchik and company collectively engaged in a cathartic, swinging jam session, playing blues and standards without head melodies. Over the next three months, Garchik sorted through hours of recorded material, cutting, pasting, and reordering it into new collages. Meeting for a second time in May, the quintet recorded Garchik’s new compositions, based on reworked material from the previous session.

Garchik respects the past but isn’t afraid to disavow formality for innovation. From his youth as a bop-obsessed teenager and student days spent with Sacks and Weiss at the Manhattan School of Music, to playing with everyone from Lee Konitz to Mary Halvorson, Garchik has always been a forward-thinking artist. Although aesthetically aligned to the jazz of the past, the process of making Assembly was more like a rock record than a classic “live in the studio” jazz session. Even Teo Macero’s infamous splicing on Miles Davis’ seminal fusion albums didn’t incorporate this level of editing. Assembly doesn’t sound like a typical performance – it sounds like an overdubbed, multitracked studio creation.

From the outset, the date establishes its unconventional bona fides with “Collage,” which features two separate tracks in unrelated tempos performed simultaneously. Garchick, Newsome, and Sacks solo together over the changes, creating a complex polyphonic texture when the additional track materializes. “Bricolage” is a series of loops for Newsome to improvise over, based on Morgan’s edited bass lines. Inspired by McCoy Tyner’s “Contemplation,” the impassioned “Homage” features a trombone quartet and dual saxophones supported by a massive, overdubbed rhythm section of four pianos, four basses, and three drummers. Conversely, the verdant balladry of “Fanfare” spotlights the leader’s dulcet lyricism, while “Idee Fixe” finds Sacks soloing over rhythm changes with the fractured phrasing of a broken record, which Garchik freezes mid-solo, looping the fragment to create a cinematic background for Weiss’ closing excursion.

Playing with the tradition, Garchik uses editing, loops, and overdubs to create a surreal collage on Assembly that swings effortlessly through blues, ballads, and bebop conventions. Garchik states, “It’s like chess, an old game with fixed rules, certainly not the only game to play, but there are always new ways to play it.”

–Troy Collins

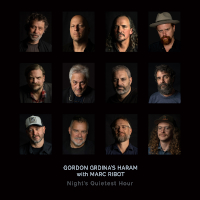

Gordon Grdina’s Haram

Night’s Quietest Hour

Attaboygirl ABG-3

To maintain creative control over his prolific output, Vancouver-based guitarist, composer, improviser, and oud player Gordon Grdina launched Attaboygirl Records in 2021 with the concurrent release of Pendulum, his third solo album, and Klotski, the debut of Grdina’s exploratory Square Peg quartet. Grdina returns with two more diverse and adventurous new Attaboygirl releases for 2022, each of which finds him collaborating with one of creative improvised music’s most innovative artists. Oddly Enough is a new collection of compositions for solo guitar written by saxophonist Tim Berne and Night’s Quietest Hour documents a meeting between iconic guitarist Marc Ribot and Grdina’s Arabic music ensemble Haram.

To maintain creative control over his prolific output, Vancouver-based guitarist, composer, improviser, and oud player Gordon Grdina launched Attaboygirl Records in 2021 with the concurrent release of Pendulum, his third solo album, and Klotski, the debut of Grdina’s exploratory Square Peg quartet. Grdina returns with two more diverse and adventurous new Attaboygirl releases for 2022, each of which finds him collaborating with one of creative improvised music’s most innovative artists. Oddly Enough is a new collection of compositions for solo guitar written by saxophonist Tim Berne and Night’s Quietest Hour documents a meeting between iconic guitarist Marc Ribot and Grdina’s Arabic music ensemble Haram.

Oddly Enough came about during Covid lockdown. At the outset of the pandemic, Berne sent Grdina a new piece for solo guitar, who sent back a recorded interpretation. That back and forth continued for almost a year before there was enough material for an album. In contrast to his solo efforts, Haram is Grdina’s most ambitious project to date. Grdina founded Haram in 2008 to further develop his work with traditional Arabic and Iraqi folk music in cooperation with several Vancouver-based improvisers. The 12-piece ensemble employs ancient instruments like ney (end-blown flute), darbuka (goblet drum) and riq (Arabic tambourine), as well as an array of brass, reeds, strings, and percussion. Night’s Quietest Hour, the follow-up to Her Eyes Illuminate, the group’s 2012 Songlines debut, features Ribot as invited guest soloist, who joined the ensemble in Vancouver for a pair of concerts and a recording session in early 2020, shortly before the onset of the pandemic. Comprised of three pieces written by Arabic composers (Kevser Hanim, Salah Ben Al Badiya, and Ahmad Al Jaberi) as well as two traditional tunes, Haram’s sophomore effort evokes sweeping Middle Eastern modalities, much like Amir ElSaffar’s Rivers of Sound Orchestra.

The set opens with the hypnotic “Longa Nahawand.” Ribot and Grdina (on oud) play stirring variations on the central motif while various members solo and interact. The unwavering backbeat of “Sala Min Shaaraha A-Thahab” provides a solid foundation for the impassioned vocals of Emad Armoush and ample space for Ribot, whose raw, punk rock aesthetic imbues this cut – and the rest of the proceedings – with vim and vigor. The leader’s dexterous oud playing is featured prominently on the traditional “Dulab Bayati,” while different musicians interweave throughout the ensemble sections. The lush opening of “Lamma Bada Yatathanna (When She Begins To Sway)” provides a brief respite, until “Hawj Erreeh (Violent Wind)” closes the album on a rousing high note. Cohesive and evocative, Night’s Quietest Hour is a seamless fusion of Middle Eastern melodies, compelling ensemble work, and impassioned solos that will transport attuned listeners to another time and place.

–Troy Collins