Jumpin’ In

a column by

Greg Buium

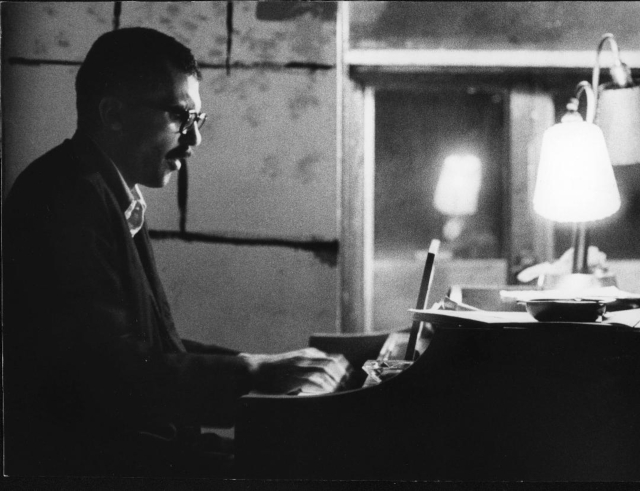

Paul Bley, Gary Peacock + Pete La Roca, 1963 ©Sy Johnson

Jumpin’ In this issue features an excerpt from the author’s work in progress, a biography of pianist Paul Bley.

****

Even now, after all these years, Gary Peacock still isn’t sure how Paul Bley got his number.

It was late 1958, or 1959. After a youth spent studying a variety of instruments, and a stint overseas in the United States Army, Peacock was back in Los Angeles trying to make his way as a musician – this time, as a bassist. He’d been a late starter. He was twenty when he picked up the instrument for the first time; he’d been at it now for barely four years.

“You working Friday night?” Bley asked.

His telephone call had come out of the blue. It was about a job: a duo, Friday night, at a coffeehouse on Sepulveda Boulevard. It paid five dollars.

“I thought, Wow, five bucks – that’s better than two!” Peacock remembered. “I would have worked with the carnival. I would have done anything just to stay alive.”

He knew very little about the pianist, a Canadian, three years his senior. In those days, Peacock’s turf was the Los Angeles mainstream. He revered bassist Red Mitchell, and counted him as a friend. Peacock hadn’t yet come across the new music – being played mostly in private rehearsals and informal jam sessions around town – a world Bley himself had only recently discovered, fully formed, through bandmates at the Hillcrest Club, his longtime gig in a largely African-American section of Los Angeles. Peacock hadn’t been to the Washington Boulevard club that fall, when Bley had famously invited alto saxophonist Ornette Coleman and trumpeter Don Cherry into his band – a quintet that already included bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Billy Higgins (Coleman’s future rhythm section). This would be the saxophonist’s only public engagement of 1958.

Still, Peacock was keen to make an impression Friday night. He remembered getting to the gig early, pulling the cover off his bass, setting it down next to the piano. It was an old, unfortunate upright – and completely out of tune; it would be a struggle to tune his bass. He went to the bar and ordered something to drink.

“I’m sitting there and all of a sudden I heard the piano: somebody’s checking out keys on the piano,” Peacock said.

“And I looked over and there’s this guy there with a hat on and an overcoat. He keeps punching the piano like this,” Peacock said, imitating the stranger’s motions, striking each key, one by one. “I better let him know that there’s going to be this music so he can find a place to sit. So, I went over and I said, ‘Excuse me, sir, but we’re going to be playing some music in a while. You might want to find a ...’ He looked around and he said, ‘Gary?’ And I said, ‘Yeah?’ He said, ‘I’m Paul. Let’s play.’ ”

Six decades later, sitting at the kitchen table in his Olivebridge, New York home, Peacock breaks into terrific, I-still-can’t-believe-this laughter. “You know ‘These Foolish Things’?” Bley asked. “Yeah, yeah,” Peacock replied. The pianist quickly barked out the key: E.

Peacock paused. “And so I think … E? He must have meant E-flat? Nobody plays it in E.

“So we started to play. And I remember thinking after the first bar, Yeah, he meant E-flat. So I moved immediately and played it in the key of E-flat. Immediately, he turned around and said, ‘E!’ So he’s playing the melody and the changes in one key and I’m a half-step away playing the roots of chords in another one and it’s like ...”

Peacock stopped. He scrunched up his face: the music was excruciating. “And the piano’s out of tune! It was, like, holy shit. It just didn’t work. But then ... it did start to work. Something was shifting in the ... ooh, that was interesting ... oh, this is interesting!” Peacock again began to laugh. They kept going, right to the end of the song.

“That was my first introduction,” he said, knocking the tabletop with each word, as if to add an exclamation mark to his memory. “It was like: Who is this guy? I mean, yeah, I’d heard something about him, but this was pretty out.”

****

Irresistible, I-still-can’t-believe-this stories have followed Paul Bley around since he was a kid growing up in Montreal. Usually, he was the master teller of his own tales. At his death, in January 2016 at the age of eighty-three, he was widely hailed as one of the most influential pianists in jazz history – and, despite a stiff argument from Glenn Gould’s and Oscar Peterson’s constituents, perhaps the greatest Canadian to ever play the instrument. He was also – by his own admission – a lifelong hustler, an unabashed self-promoter. One later-life friend, pianist Frank Kimbrough, called him “a raconteur for the ages.” Stopping Time, Bley’s 1999 autobiography, written with another Canadian, author and musician David Lee, was filled with perfectly formed vignettes, many of which he’d told and retold for years – finding Charlie Parker in a Manhattan basement in the winter of ‘53, inviting him up to the Jazz Workshop in Montreal, then never letting him out of his sight (until after the gig and the saxophonist had safely boarded a flight back to New York); or perhaps driving nonstop out of Los Angeles in August 1959, arriving in the Berkshire hills, on the New England side of the New York-Massachusetts state line, just in time to sit in on the last tune on the last night of the fabled Lenox School of Jazz. The stories were inexhaustible; his allegiance to the facts was often open for debate. Stopping Time dared you to separate the artist from the art. Shortly after the book was published, Bley suggested that an autobiography is simply “a collection of self-serving anecdotes.”

In his telling, Paul Bley’s musical life may have seemed overlarge – but in many ways, it really was. He grew up when giants walked the earth: his first recording, at 20, came out of that Jazz Workshop performance with Charlie Parker; his first as a leader, nine months later, featured bassist Charles Mingus and drummer Art Blakey – as sidemen – on Mingus’ label, Debut Records. In subsequent years, he would gig with saxophonists Ben Webster and Lester Young and in 1954 he would share an extended New York engagement with Louis Armstrong’s band at Basin Street East.

But to meet the pianist in the late fifties or early sixties – as Gary Peacock did – was something altogether different. In those early days, after he’d encountered Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry for the first time, as he’d begun to digest, in earnest, their radical new music, he devoted himself to its revelations. He’d had intimations of the next step before: hearing Lennie Tristano’s band when he first landed in New York in 1950, then later, at the pianist’s private Saturday night sessions, among the most experimental music of the time; or intermittently, in his freely-improvised duets with Canadian trumpeter Herbie Spanier, most notably in Los Angeles in 1957 when they performed at the Crescendo, Gene Norman’s legendary Sunset Boulevard nightclub. These were musicians looking past bebop, towards a newer, freer form of modern jazz. Coleman and Cherry were going even further. Their example stuck: they pointed the way forward.

“How the piano dealt with this situation was completely up to me,” Bley wrote in Stopping Time. “This was one of the three times in my life that I possessed information that nobody on the planet had as a keyboard player. I was unique in having to deal with translating that music.”

The situation thrilled him; he admitted to being daunted by it as well. “Having a piece of information that no one else on the planet has is very exciting, but in retrospect it can be dangerous, and my motto now is I would prefer to be second or third rather than be first. First is the hard way.”

And so, how did he proceed? After the Hillcrest Club, Bley wrote in Stopping Time, he “headed down the road looking for opportunities to sit in, to see how all this related to music in California in 1958.” There was a short-lived band that included a local teenage vibraphonist, Bobby Hutcherson. Sometime during this stretch he met Gary Peacock. Any recordings he made during this period haven’t survived; very little has been written either. After driving to Lenox that summer, Bley settled in Manhattan for good, or at least until he moved upstate, to Cherry Valley, more than two decades later.

Being on the bandstand with Paul Bley in those days was a singular – sometimes searing – event. The spirit of Peacock’s story is repeated, over and over again: Bley was often inscrutable, elliptical, wondrously proficient, and nearly always out of reach. His entire approach was sui generis. Without saying a word, he could unmoor an accomplished musician – forcing him to re-examine the foundations of his craft. He might call a song, reconfigure it straight away, or flip it upside down; the next time, he might not even call a tune at all.

“I think when he came to New York [in 1959], he really just was beginning to absorb all of what he’d gleaned from his experience with Ornette,” observed arranger, orchestrator, and pianist Sy Johnson, who met Bley in Los Angeles in the summer of 1957. Johnson, an accomplished journalist and photographer as well, is responsible for many of the now iconic images of Bley, including the cover photographs to both his ESP-Disk recordings, Barrage (1964) and Closer (1965).

“He was trying to find an independent approach to the music that equaled the freedom that Ornette felt,” Johnson said, then noted that, interestingly, Bley never abandoned standard songs. “He was trying to find a way to get into that no man’s land that Ornette inhabited so effortlessly. Of course, Ornette had his own code, his own laws – he was pretty organized. And the guys who played with him knew Ornette’s point of view about playing the music. But Paul never gave anybody that luxury of doing that.”

Off the bandstand, he might be voluble. (“Paul Bley is the most opinionated person I have ever known,” wrote Carla Borg – soon to be Carla Bley – in the liner notes to Solemn Meditation, her partner’s 1957 album.) On the bandstand, he could be practically mute. When bassist Steve Swallow met Bley for the first time, in the hours before a trio concert at Bard College in November 1959, he asked if there was any music he might look at beforehand. Bley said no. Swallow, 19, then in his second year at Yale (a Latin major), had driven up to Annandale-on-Hudson, New York that afternoon for the gig.

“So I asked him, ‘What would we be playing?’ hoping that he’d kind of give me a list of tunes,” Swallow remembered. “And he said very tersely, ‘I don’t know’ and kind of left it at that. I thought that was extraordinary. I’d never worked for a leader who wasn’t kind of overeager to prepare me as best he could for an utterly unrehearsed performance. But here was Paul doing the exact opposite, rebuffing every attempt I made to have any idea what was going to happen.

“By the time we actually hit the bandstand, I was in a tizzy. I had never before gotten up in front of what seemed like a huge crowd to me; it was probably a few hundred Bard students, but it seemed like an endless sea of people. I was up on this bandstand with no idea what I was going to do. This had never happened before. I had never faced a concert without an idea of what even the first song was to be. And as I recall, Paul did what he has often done over the years. We got to the bandstand and he simply sat at the piano, very composed and still and silent. This did nothing but increase my anxiety by leaps and bounds. Here we were, standing in front of an audience, doing nothing – and, again, this was something I had never experienced before.”

It was, to both Swallow and Peacock, an unforgettable first impression. It altered their lives forever. In Swallow’s case, he finished the performance – just three songs – and drove back to his Connecticut dormitory later that day. Early in the new year, he quit school, moved to Manhattan, and, unannounced, made his way to Paul and Carla Bley’s tiny East Ninth Street apartment. “I just kind of presented myself at Paul and Carla’s doorstep – just knocked on the door and said, ‘Your bass player is here,’ ” Swallow remembered. “And to their credit they welcomed me in and accepted me and I began working with Paul immediately, playing duo with him in the coffeehouses.” For Peacock, he soon discovered Coleman’s music (inadvertently, through one of his bass students) and, by 1962, when Bley called again – this time, to join a record date with trumpeter Don Ellis – he, too, was ready for New York. That winter, he shipped his bass and drove east. Paul Bley was the first person he called when he got to town.

Paul Bley, circa 1961-2 ©Sy Johnson

****

This new music often entered the world in wildly uneven conditions. That late fifties ecosystem – of coffeehouses, bars, nightclubs, and lofts – in Los Angeles and then in New York, was especially fertile. For a time, venues could be remarkably open-minded; at first, they weren’t cowed by “free music,” as it was soon called. But there were limits. Tiny, indifferent, even hostile audiences (especially in bars further afield) were not uncommon. The pay might be poor, for the door (without a guaranteed minimum), or non-existent. Pianists were often faced with truly desperate instruments: broken-down uprights were a professional hazard.

This became Paul Bley’s natural terrain. “I’m sure if you’ve talked to a bunch of people about Paul that it’s come up that he loved eccentric instruments,” Steve Swallow said. “He loved instruments with foibles. You know in the circles we were traveling in those days we were playing an endless succession of barely maintained, out-of-tune pianos. And Paul just took delight in the eccentricities of all the pianos we were encountering.”

Bassist Barre Phillips, who met Bley in Greenwich Village in the autumn of 1962, still remembers the only gig they played together in those days, a quartet with trumpeter Alan Shorter and drummer Robert Patterson (before he became Rashied Ali). “This piano was clapped-out, man. It had at least six notes that were broken. The key was there but it didn’t do anything, the hammer was broken off or whatever it was. This old upright. He managed to play that gig without using those notes. He did not touch those broken keys. We were improvising (and sometimes wildly!) and my jaw was falling down. I thought, How on earth could you do that? It’s, like, all of a sudden I’ve only got three strings to play on and it sounds just like a four-string bass.”

Bley wasn’t always so accommodating. Bill Smith, then art director of Coda magazine in Toronto, on one of his early trips to New York, remembered meeting the pianist at the Five Spot. Bley was slated to play with Charles Mingus’ band. “He wouldn’t play – because the piano was so out of tune!” Smith said. “I thought that anyone who would dare to say no to Mingus would probably be killed right on the spot. But they just played without him. Paul just came back down [off the bandstand]. The piano was terrible.”

In his later years, Bley seemed happy to forget these hurdles. He now expected to see a Steinway or a Bösendorfer at a gig. He came to play, and admire, some of the finest instruments at many of the world’s greatest concert halls. When asked about the working conditions he once faced, Bley would toggle between humor and disdain. He admitted he could now be cruel in his judgments.

W. Eugene Smith’s loft, the subject of a recent book and documentary film, was a frequent destination for Bley’s crowd. Smith, a longtime Life magazine photographer, and one of the pioneering Second World War photojournalists, kept his Sixth Avenue space open day and night – for musicians and artists and an entire cast of underground characters. Saxophonist Zoot Sims was said to be Smith’s favorite. Thelonious Monk and Hall Overton rehearsed the famous 1959 Town Hall concert there. In 1960, Steve Swallow lived down the street (in a loft of his own). For a short time, the Bleys lived nearby as well.

In 2004, while writing The Jazz Loft Project, author Sam Stephenson interviewed Bley in Cherry Valley. Stephenson showed him old, previously unseen photographs of the space; he played audio clips from Smith’s huge stock of homemade reel-to-reel tapes, including some marvelous material with Bley and Rahsaan Roland Kirk.

“What do you remember about the piano?” Stephenson asked near the beginning of their conversation.

Bley put down his cup of coffee, and broke into sharp laughter. “How much tape do you have?” he asked. “Let me tell you a Steve Swallow bassist’s joke about my piano playing, which reflects upon this period. He said, Paul Bley is the only pianist he knows that can make a grand piano sound like an upright. And I had plenty of training in Eugene’s loft. It was so primitive! We won’t even talk about the upright. But when the drummer came in, he would play brushes on top of the New York telephone book – the Yellow Pages, as I recall. There was drums sometimes; there was no drums other times. It was a very handmade session.

“And the piano?” he continued. “Well, let’s put it this way: you wouldn’t want to waste the match.”

Together, Bley and Stephenson took delight in the quip. “We’ve been told that it was a Baldwin – is that what you remember?” Stephenson asked. “Well, whatever it was, it was a wreck,” Bley replied.

Ask Steve Swallow about Gene Smith’s place, and he, too, remembers it vividly – from a perspective we might, ideally, add to Stephenson’s transcript. Their circle, Swallow said, frequented the space simply because it was available. But in his mind, they were also there because Bley loved the piano: he found it “particularly delightful ... In its imperfections, in its challenges.”

“Nobody had any money,” Swallow said. “So it was seldom tuned and not maintained either. But it was basically a good instrument. And I accompanied that piano in the hands of all kinds of people, from Dave McKenna to Sonny Clark to Paul. And Paul was the only guy who played the piano for its imperfections. Who zoomed like a hawk in on the notes that were the most problematic to all the other piano players.”

Swallow now paused, taking great joy in the memory. Bley, he said, somehow incorporated the instrument’s shortcomings into whatever he was doing “and then made a solo, exploiting the character of that particular piano – and of all the other ones, up and down Sixth Avenue, and across 23rd Street,” a part of town that had then become a hub for their community.

Gary Peacock, too, remembered with affection, and with amazement, how Bley handled these difficult instruments – especially when it came to his sensitivity to dynamics.

“Dynamics has to do with touch: how the fingers actually touch the keyboard,” Peacock explained. “I always experienced a ... I guess I would have to call it an invitation when he’d start to play. And a lot of that had to do with the way that he’s pushing a note down on the keyboard. It’s almost like somebody walking up to a house and somebody opens the door and is asking you in. Something about that sound. I’ve experienced it with Keith [Jarrett], yeah, but I didn’t experience it with Herbie Hancock. I think with Bill Evans, yeah, there was some of that. But with Bill it was more harmonic voicings that he used, although I loved his touch, too. It was incredible. But it was his whole harmonic orientation. It was like going to a feast: you walk into the room, it’s a wonderful room, incredible food – welcome. No, there was something about Paul’s touch.

“But where I really noticed it the most, was when he played on an out-of-tune piano. And sometimes in my mind it’s the best he ever sounded – when he’s playing a piano that’s out of tune.”

Peacock has long wondered how this could be true. “I talked to Keith about that. And Keith said he thought Paul sounds better when he’s playing an out-of-tune piano than when he’s playing a piano that’s in tune. So we’re hearing something that, with almost any other player, we would never be able to say that about. But somehow he was using it and accepting it, as is, without forcing it to be any other way than it is.

“Did you ever see Wozzeck, the opera? Alban Berg. There’s a scene in the second half. It’s a barroom scene. There’s a guy on a piano, and they’ve intentionally mistuned the piano so it sounds like an out-of-tune piano. But I remember listening to that – this is before I met Paul – when I first got back from Europe. I remember listening to this piano and being enthralled. Because Alban Berg actually wrote something for a mis ... tuned piano.”

Slowly, Peacock finished, leaned in, and broke into great infectious laughter. “It’s the fact that I played with pianists who played out-of-tune pianos: it was never a very pleasant experience. But with Paul? I never had an unpleasant experience – with an out-of-tune piano. Nah. He would use it. He’d use the out-of-tune piano: play a minor ninth and call it an octave. A mistuned octave!”

It wasn’t just in the clubs and coffeehouses and lofts that Bley ran into these obstacles. The record dates he led were compromised, too. A poor piano on one date; an inattentive producer on the next. These weren’t big budget operations, and they weren’t Blue Note dates either. It wasn’t until he met German producer Manfred Eicher, and recorded Open, to Love (1972), his first ECM album from start to finish, that Bley found the ideal sonic situation.

Among Bley’s 1960s masterworks, Footloose! might be the finest example of a troubled piano brought in from the cold. The album holds up as a milestone in many ways. It’s the only instance (on record) of Bley, Swallow, and drummer Pete La Roca as a unit. It’s also the first album made up largely of Carla Bley’s compositions, those now classic miniatures that came to be Paul’s signature, despite the dissolution of their marriage just a few years later. By the summer of 1962, when the sessions began, the trio was at the height of its powers – the next step Bley had envisioned when he arrived back in New York.

Swallow had, by then, become Bley’s bass player, as he’d hoped when he first moved to town. The two had been inseparable for more than two years – in duo, in a variety of ad hoc configurations, and above all, in their work in Jimmy Giuffre’s groundbreaking trio. Swallow and La Roca met on a Don Ellis date in 1961, and quickly became a pair, too, a true rhythm team – working in subsequent years with Marian McPartland, Art Farmer, and Steve Kuhn.

For the first Footloose! session, Swallow still remembers the three of them, together, driving out to the old Savoy studios in Newark, New Jersey. “There had been colossal rains the preceding couple of days and when we got there we found that the studio was flooded out, to the extent that the piano was full of water, a mess and utterly unplayable. And of course [Herman] Lubinsky, the owner of Savoy, hadn’t bothered to call us. So we’d made the trip in vain. There was no earthly possibility of recording that day. So we drove back to Manhattan and Paul arranged on the phone for the session to be rescheduled a few days hence.

“And we went back out there to the very same room. And the carpets were still spongy with water. They had somehow dried the piano out, and kind of half-tuned it. I mean, when you listen to that record you hear: it’s a miserable instrument. But Paul of course loved miserable instruments, so that wasn’t really a problem.”

Early twenty-first-century hi-fi has, perhaps cruelly, locked in the session’s scars – although that might just deepen the mystery, and the mastery, in this music. Consider three unnamed ballads, released among a series of outtakes and extras by Savoy in the 1980s. The Medallion Studios’ piano is there, unvarnished and brutal. Bley’s performance is itself raw and feels, even now, weirdly out of shape; it is also, by turns, tender and achingly beautiful. The performances are short (just four minutes each) and, to most ears, unrecognizable at first: gorgeous, off-center abstractions. Then listen again. Eventually, there’s a familiar turn of phrase here, a familiar harmonic sequence there – “I Can’t Get Started,” played twice (“Ballad No. 2,” and “Ballad No. 4”), without a glimpse of the melody, reharmonized, and stretched beyond standard AABA song form. For the first time on vinyl we’re hearing the perfectly-balanced microcosmos Bley and Swallow had been honing in Greenwich Village coffeehouses. On “Ballad No. 1” it’s only piano and bass, at an uncomfortably slow tempo, hiding “These Foolish Things” in plain sight – just as Bley and Gary Peacock might have done, in Los Angeles, only a few years before.

****

All quotations in this excerpt come from the author’s interviews, unless otherwise noted. The author wishes to acknowledge Sam Stephenson, who generously shared his 2004 interview with Paul Bley, conducted during the writing of his book, The Jazz Loft Project: Photographs and Tapes of W. Eugene Smith from 821 Sixth Avenue, 1957–1965; and Carol Goss, for graciously sharing the video she shot of Stephenson’s interview, and for her permission to include Bley’s previously unpublished words here. Thank you as well to Wolfram Knauer, Doris Schröder, and Arndt Weidler at the Jazzinstitut Darmstadt; Frank Kimbrough; and Sy Johnson and Lois Mirviss, who permitted Point of Departure to publish these exquisite photographs.

©2019 Greg Buium